PHILIP GEFTER ON BILL CUNNINGHAM

When the photographer Bill Cunningham died in June, theoutpouring was appropriate for someone who had stature equalto that of a national treasure:Front-page headlines for almost a week; tributes in everymajor magazine; remembrances flooding Facebook andInstagram; and culminating in Mayor De Blasio of NewYork City designating the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57thStreet “Bill Cunningham Way.” Bill was 87 years old and,for me, his death was not what I would call a tragedy. Heworked right up to the last days of his life, which is exactlywhat he wanted, and his exit was characteristically graciousand swift, absent any pain and suffering. Still, it leftme very sad. A beacon of goodness and joy has departedthe planet.

Bill’s combination of passion, rigor, purity, innocence,and originality set a unique standard. People who knewhim were touched by his dedication and joy; those who followedhis columns in the Times relied on his sense of styleand his unwavering eye; and audiences of strangers aroundthe world-- introduced to him through the film, “BillCunningham New York,” which my husband, RichardPress, directed and which I produced-- were consistentlyinspired by him: Not only was his joy infectious, but herewas a man who figured out how to spend his days doingsomething he genuinely loved, on his own terms. There isno greater wisdom than that.

Of course, Bill would have been embarrassed to hear thathe set a standard for anything, and his humility only madehim that much more appealing. In 2008, he was made anOfficer in the Order of Arts and Letters of the Ministryof Culture in France. The French Minister himself explainedthat Bill didn’t think he deserved such an honor.“And that’s precisely why he deserves it,” he said, with awry smile. Bill, the reluctant recipient of such official highacknowledgment in France, choked up with emotion at theconclusion of his acceptance speech, saying: “He who seeksbeauty will find it.” Indeed.

Bill Cunningham was a delightful presence—affable,charming, never missing a beat, always ready for a laugh,yet not one to stray far from the work at hand. Hewould dismiss anyone who called him a serious photographerby claiming to be nothing but a fraud. In fact, foralmost fifty years he used the camera as a “pen,” as heonce described it, a tool for reporting his two columnsin the New York Times: “On the Street” was a mosaicof pictures of people he photographed on the streets ofNew York on a weekly basis to identify evolving currentsin fashion. He had an uncanny eye for spottingwhat was new about how people were dressing. Hisother weekly column, “Evening Hours,” was a separatemosaic of pictures taken at charity balls and culturalevents where women were dressed formally for the eveningand where money was raised for worthy culturalinstitutions or social services.

Each week, “On the Street” focused on a single trendbefore anyone else had identified it-- whether ankleboots, a spontaneous revival of the Edwardian style formen, or neck and wrist tattoos in place of necklaces andbracelets. Bill’s ideas did not come from fashion magazinesor newsroom editors. On the contrary, magazinestook their cues from what they saw in Bill’s columns.Anna Wintour, editor in chief of Vogue for almostthirty years, said: “We all get dressed for Bill,” addingthat if he wasn’t at a designer’s show she had attended,she considered herself in the wrong place.

Bill was a fashion world deity, but it would haveembarrassed him to hear that, too. “Bill took a vow offashion,” says my husband, Richard, meaning that hefollowed his passion with the devotion of a monk. Billfocused on the essence of style, not the commerce of thefashion industry. He knew the history of fashion by era,by century. He was able to spot the influence of earlierdesigners on a current trend with the expertise of ascholar.

Bill’s formula for covering fashion was this: First, heattended the fashion shows to see what the designerswere presenting on the runway. “Paris educates theeye,” Bill always said, explaining that he went twice ayear for the fashion shows (while, equally, being nourishedby the architecture, the statuary, and the gardens).Secondly, he photographed women in formal dress atevening events to see them wearing couture in its intendedenvironment; and, third, he spent every singleday shooting what people were wearing on the streets.While he used the camera to document these threearenas, the photographic image was not what he caredabout— other than as a forensic kind of evidence; Hecared about his subject, clothes-- how they were beingworn and the way style evolved with the times. His loveof fabric, line, cut, shape and, ultimately, original stylepropelled him day in and day out to marvel at whatpeople were wearing. That said, he followed the newsof the world religiously and could be astute in pointingout the way a fashion trend reflected the economic orpolitical climate of an era.

For someone so obsessed with fashion, though, Billwas the least materialistic person I knew. He lived likea monk, blithely conducting his life with an absence ofpossessions. For many years, he lived in a tiny apartmentat the Carnegie Hall studios that looked like aderelict storage facility. There was no furniture and thebathroom was in the hallway. Instead, the file cabinetsthat composed his picture archive were stacked side byside with barely enough room for his single mattress ona flat board. When Carnegie Hall turned the studiosinto a school, he relocated to a comfortable studio apartmentoverlooking Central Park South. Immediatelyhe had the kitchen counters and appliances removedto make room for his files. “Who needs a kitchen andbath,” he said.

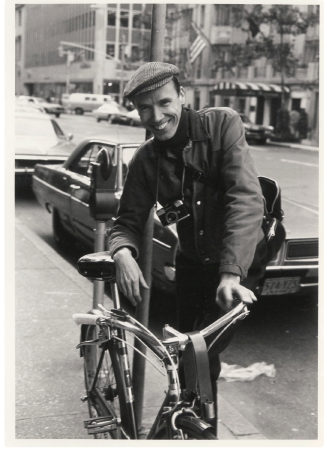

Breakfast for Bill was a quick in and out at a localdeli and dinner was often Chinese takeout before helaunched into an evening’s slate of parties. He traveledfrom one event to another on his bicycle-- his only formof transportation. He had pared everything in his lifedown to the essential structure of his work, includingthe signature blue jacket he wore, a Parisian streetsweeper’s smock he would purchase on semi-annualtrips to Paris. “They’re practical,” he explained, withfabric that withstood his cameras rubbing against it andmultiple pockets that could hold his rolls of film.

I first got to know Bill when I arrived at the Times,in 1992. He would slip furtively passed the PictureDesk, where I worked as an editor, into the photo labto have his pictures developed. I liked to ask him whathe was seeing on the street and he was happy to tellme. Then, one day, in 1994, he handed me a picture hehad taken of me several nights before at the opening ofan Avedon show at the Whitney. On the back he hadwritten a beautiful note the length of the print, sayinghe was glad to see me partaking of the cultural life ofNew York, and encouraging me to be open to the worldof art, music, theater and dance. Over the years, we establisheda meaningful rapport.

About five years ago, on a bitter cold winter morning,Bill walked into the newsroom and told me the mosthilarious story. He had covered a benefit at the Frickmuseum the night before. It had snowed and the temperaturewas in the low teens. After staying late, hewalked to the corner of Fifth Avenue where he hadchained his bicycle to a pole. Because of the weather,the lock had frozen and he couldn’t get it open. No onewas around and he started to get nervous. “Then, Ihad a brainstorm,” he said. “I urinated on the lock.” Helaughed his most gleeful laugh. “It worked.” Necessityis the mother of invention, and, as I often liked to say,Bill didn’t drop out of Harvard for no reason. In otherwords, his keen intelligence was always at play.

That night, I had a dream about Bill in which hewhispered in my ear that, in actuality, he was BugsBunny. In the dream, he shed his signature “Bill-Cunningham-blue” French street sweeper’s jacket andrevealed his true identity underneath, in the same waythat Clark Kent transformed into Superman. I wasthrilled that my unconscious produced such a dream,yet it was Bill’s ingenious way of getting himself out ofa pickle that inspired it. I had always thought of Billwith a kind of Bugs Bunny canniness, along with agood-natured, wisecracking insouciance. He could beeverywhere at once and disappear before you knew hewas gone.

That said, Bill Cunningham’s daunting accomplishmentwas that he transformed an obsession with clothesinto an exacting chronicle of the intersection of fashionand society in New York over half a century. It’s notwhat he set out to do when he picked up a camera inthe mid-1960s. Still, given his affinity for beauty, strictwork ethic, passion for clothes, and scholarly knowledgeof the history of fashion, what he leaves in his trail ispure cultural anthropology. And, for me, personally, alingering memory of his rare effervescence.